The Devil’s Business (Baby Farming)

“Baby farming” was a term coined in the 19th and early 20th centuries, referring to the practice of receiving custody of infants or children as a paid service in countries such as Britain, Australia, the United States, and Canada. This disquieting term accurately depicts a system that commodified infants and children for economic gain.

Several elements fueled the emergence of baby farming. Societal stigma towards illegitimate children and their unwed mothers, coupled with women’s restricted economic prospects, featured as key catalysts. Impoverished single mothers, unable to provide for their offspring, would compensate a baby farmer either through a one-time payment or a recurrent weekly fee for child care.

However, regulation and oversight of baby farmers were often poor or non-existent, leading to horrific abuse and neglect. Baby farmers often took in more children than they could care for, leading to neglect, malnutrition, and in many instances, death. Some baby farmers even resorted to murder, killing the children they were paid to care for. The high infant mortality rate during this period, coupled with a lack of oversight, meant that many of these deaths went unnoticed for a long time. This another case were old laws caused the death of innocents.

There were several notorious cases involving baby farmers, including Amelia Dyer in the UK, who is believed to have killed up to 400 infants in her care, and the Makin couple in Australia, who were found guilty of the murder of several infants. These cases and others caused public outrage and eventually led to legislative changes.

In response to the horrors of baby farming, governments introduced laws to protect children and regulate those offering childcare services. For instance, the UK passed the Infant Life Protection Act of 1897 and the Children Act of 1908, which included registration and inspection provisions for individuals taking care of infants. In Australia, the Child Protection Act of 1896 was introduced, which led to a licensing regime for baby farming.

Baby farming as an institution declined with the introduction of these laws and societal changes that reduced the stigmatization of illegitimate children and single mothers. Today, the practice is looked back on as a dark chapter in the history of childcare.

Margaret Waters “Brixton Baby Farmer”

Margaret Waters, also known as the “Brixton Baby Farmer,” was one of the most infamous figures associated with baby farming in 19th-century England. She is known as the first baby farmer to be executed for her crimes.

Waters began her operations in London in the late 1860s. Like other baby farmers, she took in infants for a fee, promising to provide them with care and find them a home. However, the reality was grim. Instead of caring for the babies, she neglected and mistreated them, which often led to their deaths.

It is believed that Waters would accept a lump sum from the mother—often around £5 to £10, which was a significant amount at the time—and agree to look after the child. However, rather than providing care, she would neglect the children or administer drugs such as laudanum (an opium-based painkiller) to quiet them. This neglect and drugging often resulted in the child’s death.

Waters and her sister operated together, and over time, their neglect led to the deaths of many infants. The exact number of deaths is unknown.

In 1870, the authorities became suspicious when one of the wet nurses employed by Waters reported that none of the infants placed in her care lived for more than a few weeks. A subsequent investigation found five dead infants in Waters’ care, all of whom appeared to be severely neglected.

Following a trial, Margaret Waters was found guilty of murder. Her case was highly publicized and led to public outrage. She was executed on October 11, 1870.

The case of Margaret Waters brought the issue of baby farming to public attention and led to legal reforms. Specifics about her childhood, upbringing, or factors that might have contributed to her crimes are, unfortunately, not well-documented or accessible in the historical records.

The Infamous Finchley Baby Farmers Case

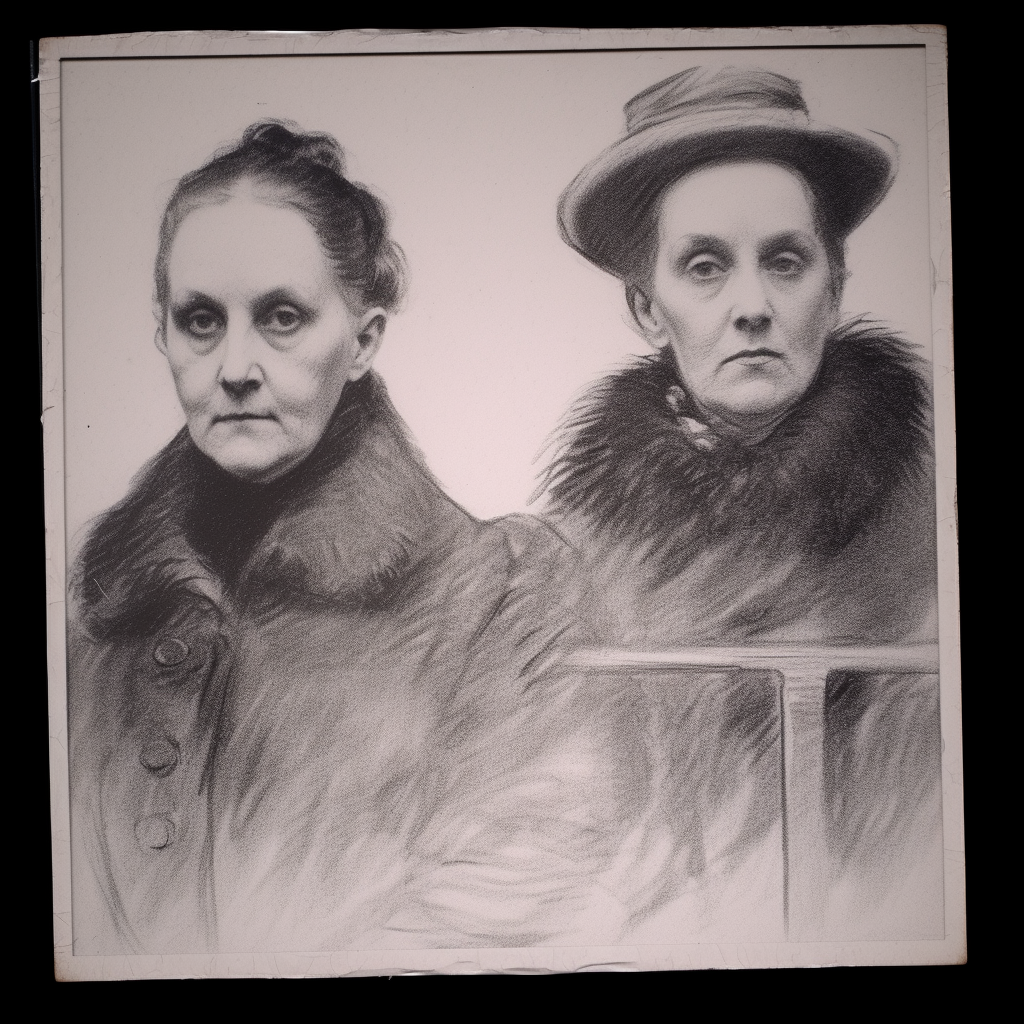

Amelia Sach, along with Annie Walters, is known for being part of the infamous Finchley baby farmers case. Operating in the early 20th century in London, England, Sach and Walters were the first women to be executed at Holloway Prison.

Amelia Sach operated a lying-in home in Claymore House, Hertford Road, in East Finchley, London. A “lying-in” home was a place where women could give birth. Many unwed pregnant women used such homes to avoid the social stigma of illegitimacy.

Amelia Sach would offer to find the babies good homes or would take care of them herself for a substantial fee. The mothers, often desperate and with few other options, would pay Sach and leave their infants in her care.

However, instead of arranging for the children’s adoption or care as promised, Sach would pass the babies on to her accomplice, Annie Walters. Walters would then murder the infants using a solution of opium known as “mother’s friend” to poison them.

Their crimes were discovered when a suspicious landlord, whose property Walters was renting, found a baby’s body. The landlord was actually a police officer, and this led to an investigation that eventually implicated Sach and Walters.

After their arrest in 1903, they were charged with the murder of more than a dozen infants. However, they were only tried for one murder due to the difficulty of gathering evidence for all the cases. The women were found guilty and sentenced to death.

Amelia Sach and Annie Walters were hanged at Holloway Prison in London on February 3, 1903. Their executions marked the first time the gallows were used at Holloway Prison.

Amelia Dyer The Most Prolific Baby Farmer

Amelia Dyer is considered one of the most notorious baby farmers in history. Operating in Victorian England, it is believed that she may have been responsible for the deaths of up to 400 infants over a 20-year period.

Born Amelia Hobley in 1837 in Pyle Marsh, Bristol, England, she was trained as a nurse and later married George Thomas. She turned to baby farming, an occupation that would prove deadly for many children, after seeing the substantial profits that could be made in the largely unregulated trade.

In a time when unmarried mothers were stigmatized and had few options, baby farmers like Dyer offered a solution, promising to take care of the child in exchange for a one-time fee or regular payments. However, the children given over to Dyer’s care did not fare well.

Dyer was known to have been mentally unstable, even being committed to several mental institutions throughout her life. It is reported that her mental health was severely affected by the death of her husband and her own mother.

She is thought to have started her murderous spree around 1869. Instead of caring for the babies she was paid to look after, she would murder them. The cause of death was usually starvation or opium poisoning, which was done to keep the babies quiet and was easily obtained at the time.

Dyer managed to evade detection for several years, partly because infant mortality was high during this period due to diseases and poor conditions, and partly because she frequently moved around to avoid suspicion.

Her downfall came in 1896 when the body of a baby girl, later identified as Helena Fry, was discovered in the River Thames. The police traced the evidence back to Dyer. A search of her home revealed shocking evidence of her crimes, including letters and advertisements from mothers looking for someone to care for their children, as well as items belonging to the infants she had taken in.

Amelia Dyer was arrested and charged with murder. She was tried at the Old Bailey and was found guilty after a jury deliberated for just four and a half minutes. She was hanged at Newgate Prison on June 10, 1896.

Information about Amelia Dyer’s early life is scarce, as is the case with many historical figures from this time period, especially those who came from relatively common backgrounds. Here is what is generally known:

Amelia Dyer (née Hobley) was born in Pyle Marsh, just east of Bristol, England, in 1837. She was the youngest of five (some sources report six) children in her family. Her parents, Samuel Hobley and Sarah Hobley (née Weymouth), worked as master shoemakers.

Dyer’s childhood was reportedly a relatively normal one until her mother suffered a severe brain injury after a typhus infection. It is believed that the lasting effects of her mother’s illness, which resulted in violent and erratic behavior, had a significant impact on Dyer. Her mother died in 1859, and it’s noted that this event deeply affected her.

She received a decent education for a girl of her class during that period, which included learning to read and write. It’s suggested that she initially trained as a nurse and later worked as a corset maker.

In 1861, she married George Thomas, a man significantly older than she was. It’s during her married life that she started baby farming – an occupation that would lead her down a gruesome path.

A Couple From Hell

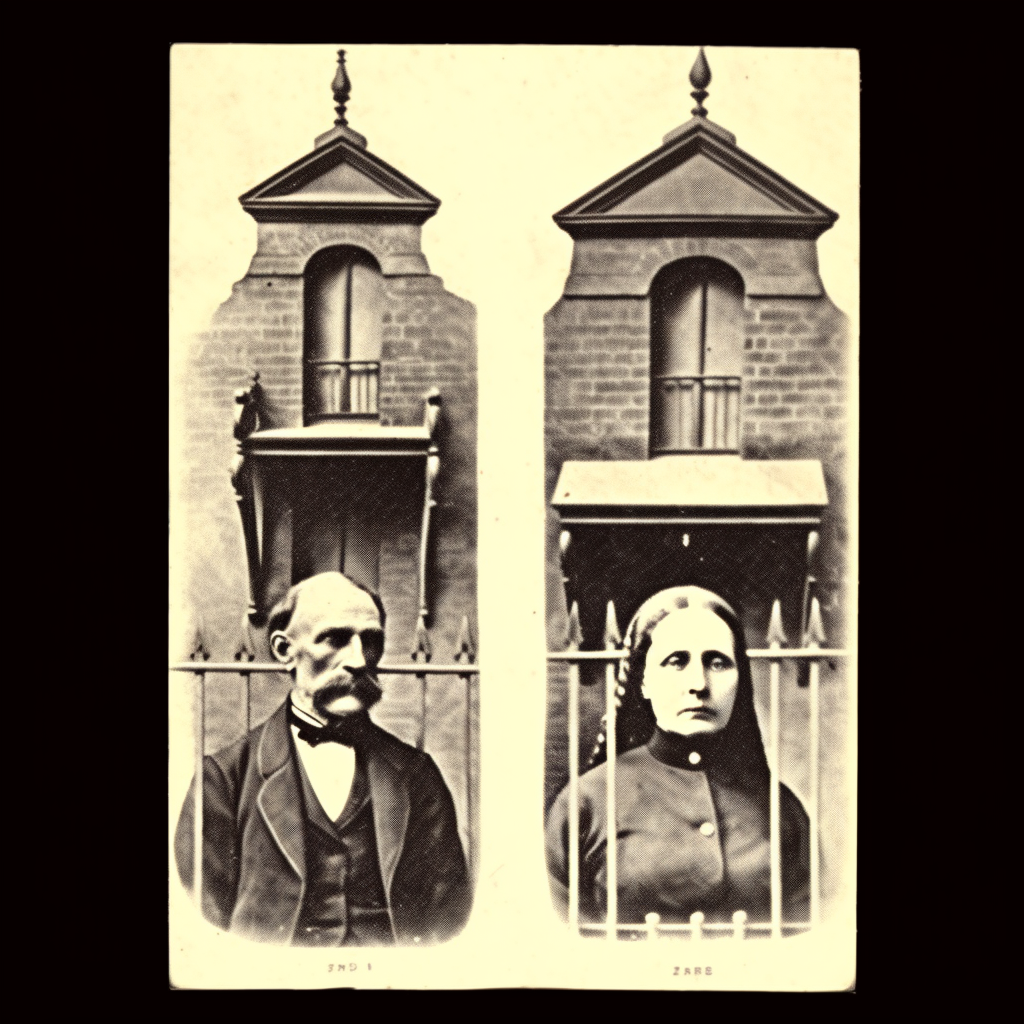

John and Sarah Makin, known as the “Baby Farming Murderers,” were an Australian couple who became infamous for their crimes in the late 19th century.

The Makins operated as baby farmers in Sydney, offering to take in infants for a regular payment or a one-time fee. However, instead of providing the care they promised, the Makins murdered the infants and disposed of their bodies.

The Makins’ crimes came to light in 1892 when the body of an infant was discovered under the floor of a house previously occupied by the couple. Further investigation led to the discovery of the remains of 13 infants in various properties the Makins had lived in around Sydney.

The evidence suggested that the Makins had taken in these infants, promised to care for them, collected their payments, and then promptly murdered the infants and disposed of their bodies. The exact methods used to kill the infants are not clearly documented, but it’s generally believed they were either starved or strangled.

Following a high-profile trial, John and Sarah Makin were convicted of the murder of infant Horace Amber Murray. While the Makins were suspected of murdering more children, the authorities chose to prosecute them for the murder of Horace due to the strength of the evidence in this case.

Both John and Sarah Makin were sentenced to death, but Sarah’s sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment due to public sentiment against the execution of women. John Makin was hanged in 1893. Sarah Makin was released from prison in 1911 due to ill health and died in 1918.

The Makin case caused a public outcry in Australia and led to calls for reform in the handling of child welfare and adoption, much like similar cases in other countries.